Are you faced with the challenge of breaking down language barriers for effective communication? Imagine…

The new African language programs in development

Various African initiatives have been developed to encourage governments to make greater use of African languages, including in the education system. ACALAN has identified 12 cross-border languages for use in regions across the continent, together with inherited ex-colonial languages. Examples include Lingala and Beti-Feng for Central Africa and Chichewa and Sestwana for Southern Africa.

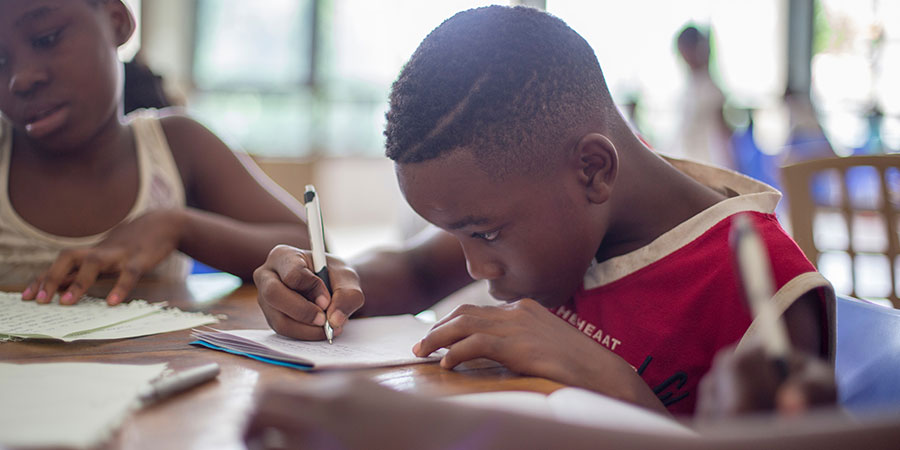

The idea is to get African languages being used as a medium of instruction, just as English is in British schools, and Kiswahili is in Kenya. For example, the Bari language in South Sudan contains five or six distinct dialects that are sometimes called ‘languages’. However, all speakers can understand one another and it is quite possible, according to some linguists, to standardize the different dialects to create one written language which could be used by speakers of all the Bari ‘languages’. This phenomenon, not unlike the Scandinavian languages, is common in Africa.

The use of the mother tongue in the early stages elicits a range of opinions. Some say African languages should be used as the medium of instruction throughout the primary level. Others favor an ‘early exit’ model whereby an African language is used for the first three or four years of schooling and then replaced by the official foreign language, which has previously been taught as a subject. A common problem with this latter approach is that children are rarely able to learn sufficient English to allow them to cope with the transition into English as the language of instruction in the fourth or fifth year of primary school, when most children are between nine and 11 years old.

What’s the solution?

It could be said that no country has got it right. In South Africa, for example, there are 11 official languages and the Ministry of Basic Education is introducing a policy whereby all speakers of English and Afrikaans must learn an African language in school. In Kenya, where Kiswahili is used as a lingua franca, this causes some confusion for some children since it is not their mother tongue. So, many Kenyan children are still being educated in a language that isn’t their own even though it is an African language. Uganda uses an early exit model, but in urban schools, English is the medium of instruction in all classes and the local language is taught as an additional language.

Some suggest that the choice of language should be decided at the school and community level and that the people themselves make the choice of which languages to use. This approach, it is argued, will most realistically reflect the languages used in the community.